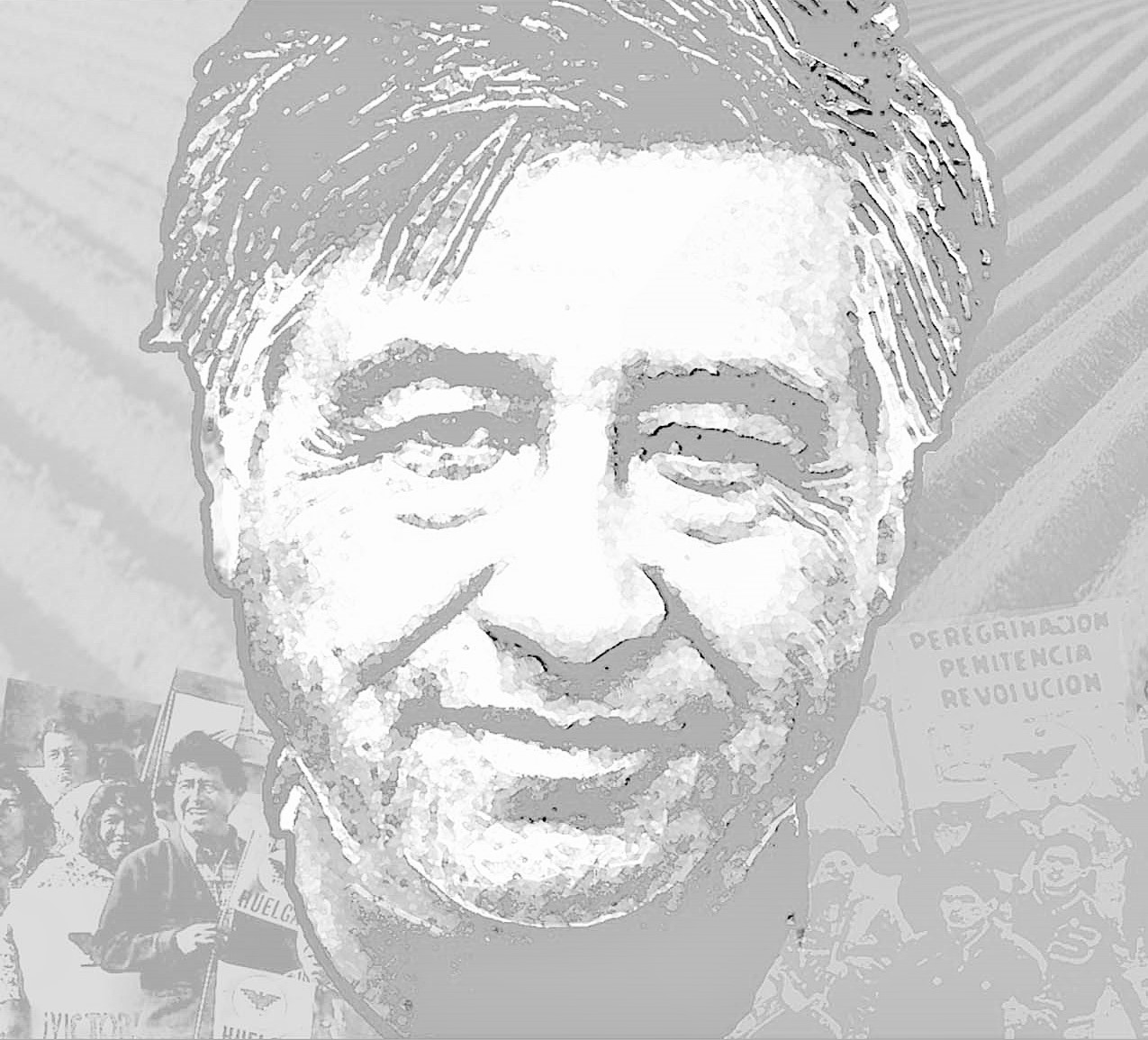

César Chavez Biography

“It’s ironic that those who till the soil, cultivate and harvest the fruits, vegetables, and other foods that fill your tables with abundance have nothing left for themselves.”

César Estrada Chávez

César Estrada Chávez was considered a giant of a man amongst social activists. During his lifetime, César experienced discrimination, prejudices, and systematic political and economic oppression, César was a visionary who lived life with a single purpose, to make the world more just and equitable for working people. It was this purpose that drove him to embrace the life of a community organizer with the belief that people have the power within themselves to improve their own lives if they are shown how to organize as a collective body. César was often quoted as saying:

“Once social change begins; it cannot be reversed. You cannot un-educate the person who has learned to read. You cannot humiliate the person who feels pride. You cannot oppress the people who are not afraid anymore.”

Against overwhelming odds and economic and political opposition by some of America’s most powerful agricultural and financial corporations, César Chávez and Dolores C. Huerta succeeded in bringing union representation to hundreds of thousands of farmworkers in California, Arizona, Texas and Florida. The benefit of their efforts to build a union of farmworkers, simple people with the humblest of beginnings, is still felt today with the enactment of hundreds of laws throughout the country designed to protect farmworkers - the hardest working people our country has ever seen.

César was a humble man shaped by economic circumstances which impacted him and his family when César was a child. Like many other small family farmers throughout the country, César’s family lost their farm during the Great Depression of the 1930s. César’s father Librado, his mother Juanita, along with César’s two brothers and two sisters, were forced to migrate to California to search for work. With his father disabled in 1942, Chávez left school while in the seventh grade to work full-time in the fields to help support his family. Traveling from town to town, César’s family was forced to live in run-downed labor camps, squalid shacks, tents, and abandoned railroad cars.

Because agricultural growers maintained a tight grip on local police and small-town governments, farmworkers throughout the country suffered many abuses and enjoyed little or no rights. Growers and their goons routinely exploited workers and their families, cheating them out of their wages, forcing them and their children to work long hours under the hot sun or freezing cold, and taking advantage of young women. There were no laws requiring growers to give workers proper tools, bathrooms in the fields, or rest breaks. Workers often had to perform inhumane stoop labor, causing them to experience severe backpain. It was not unusual for workers to be sprayed with dangerous pesticides while working in the fields. If they were injured on the job, they had no insurance to pay them for their injuries. Young children had to work alongside their parents just so they could earn enough to eat.

César would later become CSO's National Director in 1958. In 1962, César lobbied CSO to advocate for farmworkers, the most abused members of our society. When the CSO leadership turned down César’s request, César decided to leave CSO and asked Dolores Huerta to join him in forming a union for farmworkers. César believed that:

“We cannot seek achievement for ourselves and forget about progress and prosperity for our community . . . our ambitions must be broad enough to include the aspirations and needs of others, for their sakes and for our own.”

With no money and no organizational support, César - with his wife Helen and their eight children, and Dolores – now divorced with seven children, traveled to Delano, California to form the National Farm Workers Association. Their plan was to build a union by quietly and slowly organizing workers for a couple of years. Once their organization was established, they intended to call for a farmworkers’ union and take-on the California grape grower industry, the largest employer of farmworkers in the country.

In 1965, however, their plans were abruptly changed. Filipino farmworkers under the banner of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee had been organizing in the grape fields of the Coachella Valley and had some limited success in securing higher wages. When the Filipino workers started harvesting grapes in Delano that same year, Delano grape growers refused to meet the Filipino workers’ demands for higher wages and forced them to go on strike. Larry Itliong, one of the leaders of AWOC, asked César and Dolores to join their strike. With cries of “La Causa!” and in solidarity with their Filipino brothers and sisters, César and Dolores led thousands of Mexican American farmworkers on strike in what is now known as the famous “Delano Grape Strike of 1965.” César, Dolores, and Larry merged NFWA and AWOC, renaming their new union the “United Farm Workers Organizing Committee.” UFWOC would later become the United Farm Workers. The UFW would also play a critical role in creating the Chicano Movement.

César’s brother Richard E. Chávez designed the famous red UFW flag emblazoned with the black Aztec eagle in a white circle. Now used as the symbol for many social causes, the flag’s red background represents the sacrifices and commitment expected from those fighting to build a union for farmworkers, the white represents hope for a better future for oppressed people, the black represents the darkness of the farmworkers’ plight and struggle, and the black eagle represents the pride of all workers who fight for justice.

In an effort to create economic pressure and force growers to the bargaining table, Dolores Huerta convinced César to launch an international boycott of California table-grapes in 1968. By asking Americans to not buy grapes, this strategy enabled UFW striking farmworkers, who had now been on strike for almost three years, to leverage the purchasing power of American consumers. When the Delano grape growers realized that the Grape Boycott was gaining national support and that they were losing money, they hired hitmen to kill César. Even though César’s wife Helen, Dolores and César’s brother Richard were fearful that César would suffer the same fate as Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., César refused to call off the boycott and became more committed by organizing university students, labor organizations, churches, and boycott committees throughout the country. The Civil Rights Movement was rapidly spreading across the country at this same time and Mexican Americans/Chicanos in particular were invigorated by César, the UFW striking farmworkers, the Grape Boycott, and the cries of Huelga! and Viva La Causa! By 1970, more than 17 million people across the U.S. and Europe had stopped buying or eating grapes. Not wanting to fight anymore, dozens of California growers signed contracts with the UFW in the grape, lettuce, citrus, and wine industries, giving farmworkers union contracts with higher wages and improved working conditions.

After these same contracts expired in 1973, the UFW was again forced to go on strike against growers in California and Arizona. The strike became violent when growers brought in goons and thugs to beat up workers. After several farmworkers were killed on the picket-lines, César again called for a national boycott of California table grapes. Two years later, the California legislature passed the Agriculture Labor Relations Act, the first law in the country granting farmworkers the right to organize and elect a union of their own choosing.

“History will judge societies and governments - and their institutions - not by how big they are or how well they serve the rich and the powerful, but by how effectively they respond to the needs of the poor and the helpless.”

César Estrada Chávez

In the 1980s, César became concerned about the increased level of pesticides that workers and consumers were being exposed to. In 1988, César again responded with great courage by embarking on a 36 day fast to bring attention to the high-level of cancer-related deaths in farmworker communities. This fast severely afflicted his body, but it did not damage his spirit. He continued to travel across the country, including New Mexico, demanding that growers stop using dangerous pesticides on the food we eat.

His body broken by struggle, on April 23, 1993, César died in his sleep not more than 10 miles from where he was born and less than a month after visiting Albuquerque. He was 66 years of age. César was in Yuma, Arizona testifying against a lettuce grower and the State of Arizona for passing a law that made it illegal for farmworkers to boycott lettuce. The UFW would eventually get the law overturned.

In 1994, César was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by

President Bill Clinton, the highest honor our government can bestow on an American civilian. In 2012, the United States Navy named a ship in honor of César Estrada Chavez. There are many communities throughout the country that have named streets, schools, and libraries in honor of César.

César felt that:

“History will judge societies and governments - and their institutions - not by how big they are or how well they serve the rich and the powerful, but by how effectively they respond to the needs of the poor and the helpless.”

The plight of farmworkers and working people continues to this day. Many of the people that César taught to organize are now elected officials and lead major labor organizations.

¡Que Viva César Chávez!

Edited by Emilio J. Huerta, 2019